How the British Empire occupied the remote highlands of Burma (Myanmar) through football, jokes and an indomitable imperialist.

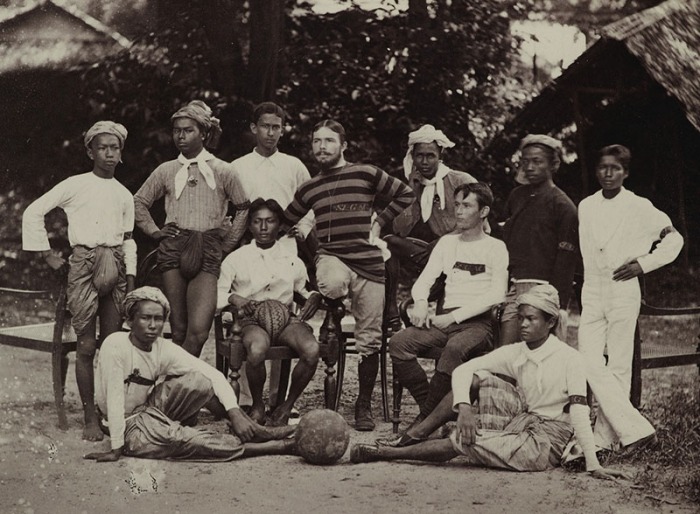

George Scott (middle, striped top) organised the first football matches in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar (Burma). 1879

One day in the late 19th century a diminutive son of a Fife preacher stood outside an unknown settlement in northern Burma.

George Scott’s expedition was beyond the protection of the British Empire and his supply route was stretched to breaking point. He was in the territory of the Wa tribe, where “every village has its skull avenue”. It was, judging by the piles of heads ripening in the sun, head hunting season. The head of a Scot or Englishman would have been highly prized. Furthermore the villagers were massed on their blockades and were not friendly.

Scott was not deterred. He stood in front of them, unarmed and alone, and told some jokes that survived translations through four different languages. Within minutes he had them laughing so much they invited his party into the village.

George Scot (1851–1935) was born for empire and adventure. ‘Stepped on something soft and wobbly. Struck a match, found it as a dead Chinaman’ recounted one diary entry. He was handsome with a well-groomed large moustache, gregarious and athletic. He had a thirst for knowledge, and was a master of language and local custom. He was a photographer, writer and a vital recorder of a world about to disappear.

Scott also introduced football to Burma, organising football matches that attracted large crowds. The Burmese, thanks to skills derived from their traditional game, caneball, turned out to be good opponents keen to exploit opportunities to beat their colonial masters.

In the mid-1880s Scott travelled to Mandalay to report on the brutal madness of the last days of King Thibaw Min’s reign. He survived some “rather ticklish situations” by nerve, luck, wearing Burmese dress and a protective Burmese tattoo. Thibaw was Burma’s last king, his reign ended with defeat by the British in 1885.

Despite their victory, parts of Burma still remained beyond British control, especially the Kachin and Shan States of Upper Burma. In 1886 Scott was sent to claim this remote wildness.

For the next 25 years Scott explored the jungle highlands of the Shan States, a region larger than England and Wales and home to an astonishing diversity of warring tribes with different languages and customs. The states were ruled by the saophas, the ‘lord of the skies’, who lived in a world of opulent courts, arcane rituals and absolute power. It was an unknown world that had not changed for centuries.

Scott tamed Upper Burma with bluff, bullying, charm and guile. He often just walked into a village, smoking his pipe and wearing a large pith helmet, assembled the puzzled locals and informed them that they were now subjects of a queen who lived 6,000 miles away. Or he would host football matches to break the ice with tribal leaders and locals. He avoided fighting when he could, preferring to use football, tea, and persuasion to achieve his aims. There was relatively little bloodshed yet when there was resistance he used the ruthless, dark practices of empire. Villages were torched and precious livestock was slaughtered. ‘We simply wiped out the village, shot everyone we saw’ read one diary entry. In later life, sad and hardened by the loss of his beloved third wife, he was cruel overlord rather than a deft persuader.

Scott was also lucky. He dodged bullets and survived fevers. His party was vastly out-numbered and walked a tightrope in negotiations and meetings with tribes, often expecting to be massacred at any point. One saopha even admitted to Scott that he would have murdered his entire party the previous night had he not been persuaded otherwise by his wives.

Considering the British did little to improve the Shan States, Scott’s legacy is that of a writer capturing a world about to change forever. His book, The Burman, was a detailed description of Burmese rituals, celebration and life. It recorded, for example, the correct method for crucifying criminals, winning strategies in Burmese chess and how to grow silk.

His Gazetteer of Upper Burma provided exhaustive details of folklore, myths and customs of the tribes. The Kachin waged war just before the moon rose, and made love in purpose-built huts. They also believed earthquakes were caused by huge subterranean crocodiles. The Banyok people worshipped their dogs in an annual ceremony. The head-hunting Wa claimed they were descended from tadpoles. There was even headhunting etiquette – beheading a man who lived on the same hill was “unneighbourly and slothful”.

Scott was not original in this. Fascinated British colonialists zealously recorded religious and ethnic differences, some would say useful information to divide and rule. Nonetheless, they left a valuable wealth of information on the ethnography of vanishing worlds.

Scott believed in empire as a civilising force but he saw an unhappy future for the Shan States. He knew the arrival of the British heralded modernity and upheaval to an old world. His efforts to initiate progress were frustrated by the saopha, who were unable to see what was happening, and the neglect of the colonial administration. Burma was forgotten compared to India, the Shan States even more so. The British exploited Burma without responsibility and occupied the Shan States more to stop France or China taking control than as part of a greater purpose. From the Shan State’s point of view worse was to come a hundred years later with war and the brutal Burmese military dictatorship.

Scott eventually retired to Sussex and his booming voice echoed through rural English life until his death. He was a forgotten imperialist operating in a neglected corner of the empire until he was plucked from obscurity by Andrew Marshall’s research and fascinating book, The Trouser People. The book also explores the traumatic recent history of the Shan States which is still not completely resolved today.

Yes but are you related? I like the purpose built hut – thinking of building one in the back court.

LikeLike

No – the Cochranes turn-up in Burma later. Such a hut would work well in the highlands of the Shan but I dread to think how it would be commandeered in the back courts and lanes of west Glasgow!

LikeLike

George Scott sounds like a man’s man. Respect!

LikeLike

He was probably extravert fun and a nightmare to hang around with at the same time. (If we of course also ignore the excesses committed in the name of empire!)

LikeLike

This sounds like an absolutely fascinating read. What an intriguing and contradictory character. And that moustache…

LikeLike

Amazing to think he ended in Sussex after all those close calls. Thanks for bringing him back!

LikeLike

Thanks Christine – he was one of those lucky, larger than life so and so’s. Lesser mortals would have copped those bullets or fevers. I can imagine him rampaging about Sussex!

LikeLike