Why did people go Nazi in the 1930s, and how does it help us to understand what is happening today with those attracted to the far right.

Would you have been a Nazi or a fascist in the 1930s? With the comfort of hindsight, few of us think we would be and yet so many were. It’s easy to judge, wiser to try and understand why, knowing what we know now, we can still fall to the lure of the far right.

In her essay, Who Goes Nazi?, Thompson, plays a macabre game at a social gathering. She looks around the room and puts each guest to the test of who, when it comes down to it, will turn Nazi. Written in 1941, her essay has a chilling relevance to what is happening today as the far-right populist politics advances across Europe. The cycle of history turns, here we go again. Lessons learnt become lessons wilfully forgotten.

Nazism, Thompson writes, has “nothing to do with race or nationality. It appeals to a certain type of mind.” This isn’t just about those with the dark triad of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. There are the simple believers of course who are already there. But some would turn Nazi or far right for career success, finance and power. This has been a common sight in the last few years with politicians shapeshifting from the mainstream centre-right to the far right, or the political influencers and hustlers who cynically follow the money and audience share by enflaming their audiences.

There’s the brilliant intellectual who is socially insecure and embittered by perceived humiliation. There’s the cold and ruthless operator, there’s the narcissist spoilt by his mother and sweet Mrs E who is a cowed masochist. There’s the corrupt union boss who has an instinct for power and hierarchy and has no principles about exploiting groups such as the Jews to stay on top.

Not everyone goes Nazi of course. There’s the man shot through with decency, secure in his standing and his moral code. There’s the intellectual contrarian who can’t help but oppose the prevailing opinion because that is who he is. There’s the happy-go-lucky actress who’s too vivacious and spirited to go along with Nazi hatred. There’s the blond German who everyone mistakes for a Nazi but passionately believes in the idea of American democracy and dynamism. The irony is, come the war, he will be interned whilst US Nazi apologists roam free.

Thompson concludes that “kind, good, gentlemanly secure people never go Nazi”. It’s the frustrated, the scared, the humiliated, the spoilt, the hangers-on: in a crisis they all go Nazi.

Thompson’s writing focuses on character and mind but it’s also worth exploring how crisis and context can torment and push good people to edge closer to the line. Once over it, they find that it’s too late to turn back because the benefits are greater for falling in with the winning side.

Imagine a state of mind that exists within us. This mind needs authority. It wants to bow to a higher power – the state, natural laws, the glory of the past. It’s a rigid simplified mindset that searches for order and hierarchical structure over freedom and ambiguity. It dislikes uncertainty and modernity. In a world where strength and power are admired, its fears being weak and despises those who are seen as weak. Their gain is your loss and because you’ve lost, now you’re a victim. Never underestimate the human need for status and dominance.

Now imagine that mind in 1930s Germany. Like many people, you care about your country and its standing in the world. Before World War One, Germany was powerful and prosperous, confident and cultured. Now you’ve seen it first defeated, then endlessly humiliated. If you don’t like a complicated world, then the disasters of the Weimar Republic are disorientating and frightening. You want things to go back to the way they used to be but the Weimar is fluid sexual identity, jazz and Bauhaus, creative, boundary-pushing. It’s also hyperinflation, exploitation, grim poverty and weak, messy politics. The communists run amok on the streets. You watch blood spill on the streets. Sexuality and gender politics is fluid and confusing. Cultural ideas are dangerous and disrespectful to tradition and order. There is a sense of your country in serious decline and under attack, lurching punch drunk from one crisis to the next. Minorities can be blamed, it’s all their fault we are being robbed of our greatness. Nothing works. The world serves no-one but a corrupted elite. Then comes the disaster of the financial crash of 1929, destroying livelihoods and lives.

Is this ringing any bells with the circumstances of today?

It’s no wonder that through the turmoil and despair, so many hear a siren call. It’s a call that offers redemption. It offers easy answers based on order, strength and power. It offers a return to virile greatness. It fuses a terrible ideology with hatred and Darwinism morality, somehow persuading you that this cause is righteous and necessary for your country and your race. Your frustration, your rage and your sense of unjust victimhood are offered an easy target.

It promises a transformation that will deliver the promised land and smash everything down. It promises something for the young, the lost generation whose future has been robbed by old men whose ways have failed. The Nazis are popular with the young just like the alt right is today.

The Nazis offer a noble thrill of self-sacrifice, pain and suffering in the struggle for destiny. It provides purpose with camaraderie, a crusade with enemies, heroes and villains. It stirs an intoxicating song in the blood. It lures you into its brutal swagger and thrilling transgression of permitted cruelty.

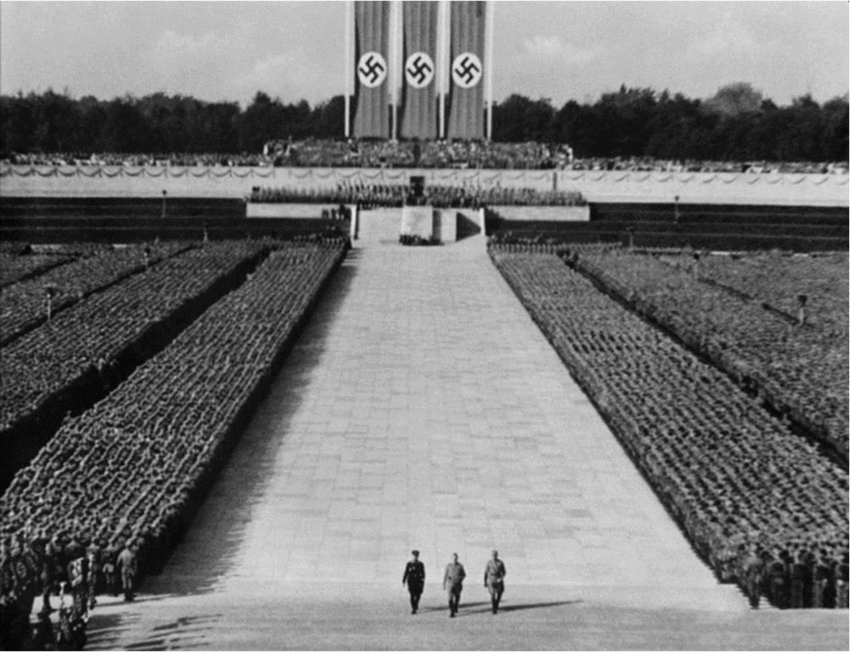

Here’s one of many uncomfortable truths about the Nazis. They knew what they were doing. They put on a brilliant and sinister show, pioneering techniques that are still used today in politics and entertainment. Watch Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will and it’s a spectacle of mass military ranks, flags and banners, flames, sentimental emotion, and ceremonial drama. Its participants dissolve into the totality so that all distinction is erased.

At its centre is a mesmerising, charismatic leader. The mistake that is made about Hiter is to forget that he was not absolutely evil but all too human, and he found fertile ground in human frailty, fear and trauma.

So, is this happening again? Right-wing populism today, like Nazism then, speaks to the social, emotional and psychological needs of citizens who have been ravaged by capitalism, modernity and loss. From Hungary to India, Israel to America, populist leaders and their supporters are certainly happy to pursue politics and culture wars with fascistic elements. Global freedom and civil liberties are in decline according to the latest Freedom in the World.

There was only one Nazism,” says Umberto Eco, but “the fascist game can be played in many forms”. His list for identifying is hitting a full house. The cult of tradition. Fear of difference. The obsession with a plot. Disagreement is treason. The appeal to social frustration. Selective populism. Add sleight-of-hand political propaganda, anti-intellectualism, obsession with law and order, the politics of sexual anxiety, attacks on cities, creating unreality to destroy the information space.

Those in the 1920s and 1930s had one excuse. They didn’t know where it was all going. Of course, there were red flags and clues, the prescient ones could follow the endgame of Nazi logic. We don’t have that excuse. We know. The truth is, as bad as our troubles have been, we’ve barely been tested compared to the violence, poverty and financial meltdowns of the 1920s and yet here we are. In the UK, the centre can and is still holding but there are an alarming number of politicians and influencers, backed by a client right-wing media, who seem far too keen to hollow it out, paranoid and obsessed by imaginary anti-woke crusades and chasing a vision of Britain that can never exist.

Today, the enemies for the authoritarian mind are those who question the order: environmental activists, strikers, judges, trade unions, anti-racists, universities, historians, socialists, charity do-gooders. Populists don’t offer solutions or any attempt to address complicated problems. It’s easier to displace frustration and rage onto low status or weaker groups: boat migrants, trans, drag queens, women, ethnic groups, those relying on welfare to survive. Punch down in fear, and hope that you avoid the same fate.

Polarisation, certainly in the UK, is still about noisy minorities. Most people are still holding the centre. But the ingredients are there for trouble, just like in other countries. The inter-connected and hyper-disruptive potential of climate change, mass migration, AI – as beneficial as it may be, and technological unreality have only got started.

Maybe, like me, you wonder what you would be like in a crisis when the time comes. What would I do if my country was committing genocide or sliding into totalitarianism? No-one thinks they are the bad guys. Everyone is a hero in their own narrative. Nor is it just about the authoritarian mind, but our moral reframing. We will draw the line and make our stand tomorrow until the chance passes, the line dissolves and now it’s just a question of fear and survival. Terror, authoritarianism and genocide become part of the system, enshrined in a banal bureaucracy. No-one is responsible because everyone is implicated and corrupted. People get on with their lives whilst evil becomes a background noise.

The answer is that for a better future, what is the point of us if we are not working towards a better society, we need to collectively face up to our truths and take our responsibilities more seriously. But human nature is tribal, fragile, weak, and geared towards group think and survival because in ancient times, to be banished from the tribe was a death sentence. Hatred, fear and othering are powerful and ancient emotions. Liberalism, enlightenment and democracy are new, fragile ideas. That’s why we must always call out fascist politics and behaviour before it builds social momentum and takes hold. It’s why there ought to be a special place in hell for those who are not fascist and know better, but still stir up dark forces for short-term gain.

And if you want to know who will succumb read Thompson’s essay and look around the room.